No shame: The story of a depressed 20-something male

For some inexplicable reason, I decided one day to withdraw from everything in my life. At the time, I was studying abroad at university in Bremen, Germany. Instead of going to lectures, I retreated into a cacoon of duvets and a world of fantasy limited to the confines of my bedroom. I shut out the outside world as if it were some vague abstraction and ignored all calls from friends and family. Instead of preparing and eating proper meals, I hoarded potato chips and chocolate in my room. The only time I went out was late at night to the nearby convenience store to buy a bottle of coke or Becks. The Sri Lankan shopkeeper noticed my gradual deterioration and asked me if I was alright. The misery and neurosis etched in my face was very apparent. My complexion had become pallid and I had dark-rings around my eyes due to poor sleep and diet. Like many people with depression, I responded “I’m fine”, knowing full well that I wasn’t.

It was as though fuse blew in my head and I felt no longer able to cope with the exigencies of day-to-day existence. During the day I slept and at night, I’d surf the internet to distract myself from the bleak reality in my head that life had absolutely no meaning. Due to my lack of activity, my body became listless and exhausted, and I could no longer cope with even the most prosaic of tasks. Things got really bad about 8 weeks into my self-imposed isolation when, foolishly, after a sleepless night I broke free from my miserable stasis and my squalid little bedroom which had become a landfill site of empty Becks bottles (some filled with pee from when I couldn’t be bothered to even get to the toilet), half-eaten stale, mouldy sausages and piles of unwashed clothes. I boarded a train early in the morning for the Dutch city of Groningen where, after a long walk in the bitter cold, I entered a coffee shop and bought a couple of joints.

I thought they’d calm me down, but they had the opposite effect, exacerbating my a deep feeling of spiritual unease that had been insidiously weaving its way into the very fabric of my being for a long time. After a few heavy tokes of my joint, I felt my heartbeat race like it never had before. I then felt the ground move underneath me. I felt like my head was being filled with some gassy, incendiary fluid and was going to explode.

I left the coffee shop hoping a blast of cold air would do me good. However, the panic failed to subside. It got to a point that I convinced myself I was dying of a heart attack and begged a passerby to call an ambulance. The girl seemed a little bemused but agreed. Before long, I was having an ECG in the back of the vehicle on one of the city’s busiest throughfares. People on the street must have wondered what on earth was wrong. After a quick check of my vitals, I was declared fine and told by the paramedics to eat some sugary food and sleep it off. I felt reassured, but still residual panic lingered and I felt strange tingling sensations on the train journey home.

The next day, I woke up feeling exhausted from the day before but resolved to clean up my act. However, the panic returned, worse than ever and suddenly I felt as though I was being sucked into a vortex of despair and agony. It was a hellish sensation. Trying to fight it only made it worse and, very reluctantly, I told my landlord who also lived in the house I was staying in that I was suffering from panic attacks. It was extremely embarrassing to admit this to somebody and a crushing blow to my self-esteem. I used to pride myself on being stoical, and yet here I was making a huge fuss about something that wasn’t even physical. Healthy males are meant to be awash with bonhomie, not enveloped by fear and despair like I was, I thought to myself. Luckily, my landlord noticed I was suffering and drove me to the nearest hospital. There, I checked into a psychiatric ward where I spent 8 long weeks getting myself fit again.

It was a surreal experience looking back on it. At times I felt fine, especially after I’d taken my medication which consisted of a high dose of Citalopram. Other times, I dissolved into undignified fits of crying and required a sedative to calm me down. Thankfully, I improved over time and was eventually able to find my way out of the darkness and even if the depression occasionally does creep back, I now have the techniques to keep it at bay. For a long time, I vowed never to tell my story for fear of what others might think. Male pride had prevented me from opening up to the world about how fragile and sensitive I really am. But here it is. I am unashamed to admit I was in a dark place, that the world had got on top of me and, rather than opening up about how I was feeling, I retreated into a place that only prolonged my suffering.

My advice to anyone in a dark place is to talk candidly to somebody you can confide in about how you are feeling. Don’t do what I did and allow that demon in your head to grow until you can longer cope. Don’t think that hiding how you’re feeling is the right way about it. It isn’t.

Depression is not an indication of weakness, but a natural result of being a human being in a demanding and often chaotic world. To feel shame about it is to ignore what complex creatures us human beings really are and the myriad difficulties we face in our lives. The sooner you get help, the sooner things will improve for you and the more people will respect you for showing the courage to open up about how you feel inside.

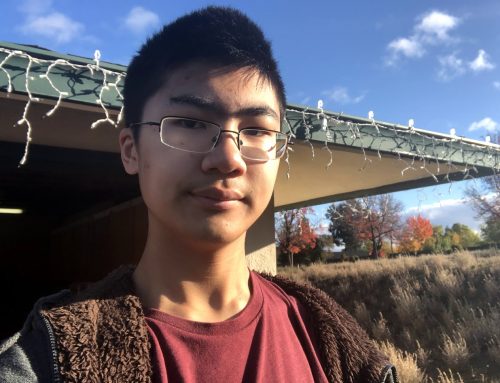

Tom Clements is a language teacher from the UK. He was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome in his early 20s and is an advocate of the neurodiversity movement. He is currently looking for a publisher for his book ‘The Autistic Buddha: An Unconventional Path to Enlightenment’.

Tom Clements is a language teacher from the UK. He was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome in his early 20s and is an advocate of the neurodiversity movement. He is currently looking for a publisher for his book ‘The Autistic Buddha: An Unconventional Path to Enlightenment’.

Tom can be found on Twitter.

Leave A Comment