My memories of the past several years are smeared, streaky and ghosted like an underdeveloped Polaroid. They are a part of my story and yet seem foggy and distant, the narrative of another person. It’s almost as if I’m the omniscient storyteller, the voiceover for a character in a movie I can replay in my head. I can watch it over and over, but in a way that is removed, slightly aloof. It is only in violent flashes that I actually recall living through these moments, that the person in the ambulance, the ICU, the treatment center, is me.

Mental illness began for me as a narrowing of my experience, a tightening of the seams, as if a thread was being pulled to hard, gathering all the stitches in one large bundle. Things that used to be spread out, allowed room for breathing, became uncomfortably close and thick. The world itself looked different from this place; the coloring was off, as if the lens I was peering through was filmy and sepia-toned. Things were brown around the edges, dull and old-fashioned, and appeared at a distance. It was as if I was always carrying something heavy and awkward, something I couldn’t figure out how to put down.

In college, doctors called it “depression.” In my mid-twenties, it was “eating disorder.” Then it was “anxiety,” then “bipolar.” And, when I still wasn’t better, it became “Borderline.”

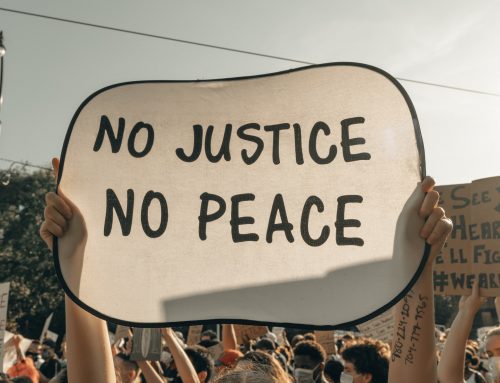

This ebb and flow of diagnoses, all very different in symptomatology, has followed me through the duration of my time in the mental health system. My experience with stigma has mirrored this as well, shifting according to my labels.

For it turns out that disclosing suicidal ideation when you are depressed warrants more resources, while revealing thoughts about killing yourself when you are Borderline is attention seeking and manipulative. Continuing to struggle when you are depressed makes you “recurrent;” when you are Borderline, it makes you “unwilling.”

As discussion of mental illness has increased, it has become organized in a hierarchical schema in the public sphere. Much like the bias of the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor, there are diagnoses that are viewed as organic and ones that are perceived as the person’s fault. This is as true in the media as it is in the emergency room or the therapist’s office; while great strides have been made in raising awareness, stigma still exists, especially around personality disorders and chronic suicidality.

I’ve been told that I’m 99.9% lethal to myself. I’ve been told that I’m an “atypical” Borderline patient because I’m so easy to work with. I’ve been told that I’m ungrateful for attempting suicide because there is nothing wrong with my life. In a meeting with my family during a hospitalization, a doctor told my parents they might as well buy my body bag now-with me in the room.

These instances stand out in the otherwise hazy recollection of my past because they are so horrifying. What is worse, though, is how such comments stopped when the label was removed from my chart. Now that I’m back to being “depressed” I am worthy of respectful care. It is as if my humanity is determined by a single word, or the absence of it.

We wonder why people die by suicide, and in the midst of the complex mess of a problem one thing stands out: silence. Is it any wonder that so many are afraid to talk about mental illness when it is so misunderstood? When seeking treatment comes with the burden of stigma and shame?

I purposely talk about my past and present struggles with mental illness with the hope that doing so will influence change. But I still feel a rise of fear when I put words like Borderline out into the world. Most of the time, I try to explain what I’ve gone through without the labels, for these small words that somehow hold such power do nothing to actually capture the reality of experience. And the reality of my experience has come down to moments.

Moments are tricky things to catch. They dart about like tiny fish weaving in and out of kelp forests on the murky ocean floor. If you look at the right time, you can glimpse the silver flash of sunbeams on scales or the flurry of tail-brushed sediment as it rises. It’s more likely, though, when the water is especially deep and dark, that you miss the movement altogether, that what you see is the vast dimness spread before you rather than the brief bursts of activity and light.

It’s so difficult, then, to do what is necessary and helpful in the moment, for when it is most vital, it can seem impossible to recognize it as a moment. If you can’t separate out one moment from the next, if time seems to blend together in a mess of blackness, then reaching out and grabbing the flashlight takes an unbelievable act of courage and strength. And then you must turn it on.

It is almost as if you have to go backwards. You can only see the moments after you turn the light on them, after you know to squint your eyes and wait patiently for the fish to emerge, even for a second, from the swirling seaweed. To do the hard thing in the moment, you have to leap and act even though it feels like you will have to act forever, that it won’t do any good because this doesn’t feel like a moment at all but a lifetime.

It’s standing up and moving one foot in front of another, forcing your legs to follow a path you can’t see, making your brain discount the panic and fear and total darkness that it’s registering and go into action without tangible reason, without any light or guidance at all. Moving when you can’t see what’s ahead of you; that’s an incredible act of bravery.

And so-moments. Because focusing on them is the source of hope when the world narrows, the thread tightens. And in shining the light on these moments and how they feel, beyond labels, above single words, is the only way to expand the minds of people who have never experienced such things, to break the silence.

Sarah Clingan is a graduate student in social work and writer, and she is passionate about raising awareness around mental illness and suicide. She is a member of the Now Matters Now project, a website of skills videos for reducing intense emotions and suicidal thoughts created by people with lived experience.

Wow. Powerfully written. As a fellow ‘borderline’ some of the responses you’ve had astonish even me (doctors mentioning body bags is just shockingly unethical and simply cruel). Your description of the experience is so powerful and resonated deeply, I am so very very glad you have expressed this so rawly and really.

Incredibly powerful and well written. I’m blown away. Your experience with varying stigma attached to different diagnoses is all too prevalent. Many of us have internalized that stigma, so we must fight on two fronts – within and without. Thank you for sharing your story.