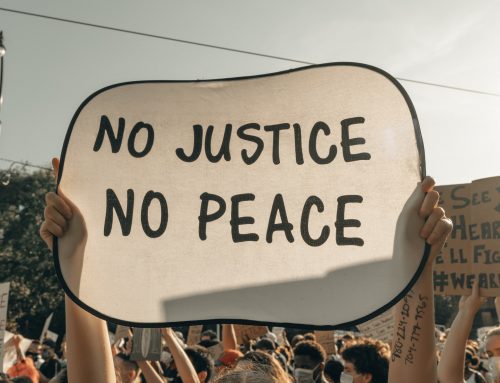

Eating disorder sufferers receive a lot of blame for their condition. People see the behavior, but they don’t see the illness. That’s because it’s a mental health condition; while you may see what’s happening on the outside, you can’t see the actual sickness. You can’t see what’s going on inside, and because of this, mental health conditions are often misunderstood. It’s easier to see a physical wound and think, “whoa, that looks like it hurts – take it easy” than it is to see an internal battle and do the same. If you have a loved one that’s recovering from Bulimia and struggling, it’s likely that you want to help but don’t know what to say. At the end of the day, I believe that most people are good; they have the best intentions, they just don’t know what to do. That’s why I want to tell you today about the power of compassion and why it isn’t coddling – it’s actually the best and most productive response.

To give you some background, I’ll tell you a little bit about my story. I have Bulimia. It started when I was eight years old. At age fourteen or fifteen, it shifted into anorexia, and the two disorders proceeded to battle each other in my head up until, well…now. I’m in recovery, and like everyone else, I have good days and bad days. I have slip-ups and I have victories. I’ve reached out to friends on my bad days, and the most helpful response was from someone who met me with open arms and no judgment. He met me with empathy and was there to listen.

Something that’s important to understand about mental health in general is that it’s not simply a matter of behavior; we have a battle going on in our brains that we aren’t a part of. We’re the host, and the eating disorder is the intruder. Having an eating disorder is like having a set of toxic, abusive parents in your head. They’re yelling and fighting, telling you to do things that’ll hurt you, and convincing you that this is for your own good – even when it’s killing you. The screaming overcomes our rational mind until we learn not to let it (more on that later), and eventually, the screaming goes away or turns into an infrequent whisper. That said, it takes time and practice to get there.

Living with an eating disorder is scary. It is a traumatic experience for the sufferer (both mentally and physically). Often, it’s scary and traumatic for the people around the sufferer, too. I understand that you’re mad at the condition. I understand that you want it to go away. I understand that you don’t want your child, friend, sibling, or significant other, to purge again. You’re afraid for their lives. Trust me, I’ve been on both sides of the coin. Say that your loved one – a friend, for example – comes to you after a slip-up. They might feel helpless, and you do, too. What can you say in this scenario? That’s where compassion comes in.

The least helpful things that I’ve heard are:

“You’re wasteful”

“Just don’t do it again”

“Great” (and a variety of other sarcastic or angry responses)

The most helpful things that I’ve heard are:

“I’m here for you”

“That sounds very painful. Do you want to talk about it?”

“I’ve heard that that’s really tough and that it’s a hard thing to fight. How can I support you?”

People with the more harsh responses, I believe, are concerned about coddling the sufferer. I can assure you that that’s not the case. Remember, the sufferer is a victim of the illness. We can get better – I’m doing it, I would know – and shame is never going to help us. Open-ended, compassionate responses will. This is because while the illness is bad, we are not. Trust me; the illness is more aggressive and brutal toward us than it is to anyone else. Harsh, sarcastic, or angry responses do a couple of things, and none of them are helpful. Historically, hearing these things have made me feel like I can’t open up to the person anymore.

When I hear “just don’t do it again,” I feel deep shame. I feel misunderstood and like I can’t come to you in the future when I am hurting. Remember, I am in recovery, and recovery isn’t linear. Recovery typically comes with slip ups and messy days (a lot of them). It takes some people six months, and it takes other people six (or more) years to be free from their eating disorder entirely. For someone like me, who has been struggling from a young age, the latter is more likely to be true. This dictator that lives inside of my head has been present for a very long time, and what I’ve learned is that being kind towards myself and gently asking myself what I need and what was going on when I used a behavior is what has led me to a dramatically improved condition. When my friend met me with love and kindness, he gave me a hand in taking care of myself and remembering that Bulimia isn’t me, which helped me reinforce that there’s a life for me without Bulimia.

Again, I have good days, and I have bad days. That’s recovery. Some of us fall down a lot when we’re learning to live a life without our eating disorder, and the painful days where we use an eating disorder behavior like purging are tough days. You might even ask someone what they need or what they think spurred the behavior (in a non-accusatory way). You’ll usually be surprised. When I binge and purge, I usually did it because:

- My head was spinning. I was too anxious to take the space to understand that I need to use a healthy coping skill (because recognizing when you need to use a new coping skill is a process)! *note, I have several diagnosed anxiety disorders that largely play into my eating disorder. While comorbid mental health issues aren’t always present in an eating disorder sufferer, they are common.

- I was overwhelmed and needed a break from something! I wasn’t giving myself the space to take a break from a conversation, from something I was working on, etc. I was I needed to rest, and I wasn’t giving it to myself. I’m used to being a people-pleaser, used to sacrificing myself to show up or to be “on,” and I’m in the process of learning when I need to take a break and use self-care.

- I was in a situation that I didn’t know how to handle in recovery yet. Say that there was a trigger and that my current set of coping skills that are adequate and practiced enough to get me through the trigger safely are yoga, art, writing, going outside, reading about a topic like science or astrology, and meditating, but that in this scenario, none of those things were readily available to me. After the slip-up, I can say to myself, “what did I need in that moment?” and think about a coping skill (like mindfulness, for example) to use next time.

Now, these are only scenarios that tend to drive my personal eating disorder behaviors. Triggers may be different for your loved one, but one thing that’s true for all of us is that recovery is a massive learning experience. Think about a child learning common safety measures like looking both ways before you cross the street – they might not remember to do it for a while, but it gets easier over time and eventually becomes second nature. Your brain takes time to adapt and change, which is what’s happening as we move through therapy and learn new patterns (CBT and DBT helped me a lot in this process, personally). In recovery from Bulimia, we’re learning a skill set that not everyone needs to learn, but that is integral to us. You don’t have to understand, but what you can do is be kind. Meet people with open arms the way that my friend did. Understand that you don’t really know what it’s like to be in their shoes. No one asked for this illness, so don’t judge the people who live with it. Like with any illness, it’s the luck of the draw; it could happen to anyone, even you, and when you get a diagnosis, all that you can do is take on the treatment, feel your feelings, and work to get to a better place.

Sometimes, I have to remind myself that having an eating disorder is literally a brain difference. Something is wrong with my brain; it’s not my fault that I have it, and all that I can do is choose to pursue recovery and keep going. It’s hard, and it might take a long time, but I’m determined to make it to the other side. Having self-compassion has been deeply important for me – in fact, the most important thing for me – in addition to accepting compassion from others in recovery. I often have to remind myself that shame is unproductive and that all I can do is accept the circumstances and make the next move in the right direction. I want to take the time to say thank you to everyone who has been compassionate towards me while I work through recovery; you’ve reinforced for me that there’s good in the world and have given me a hand up in learning to believe that I can do this. To anyone who is in recovery as well, I want you to know that I’m right here with you. You’re not alone. We can change the statistics and live our best lives.

*If you or a loved one are struggling with an eating disorder, please visit https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/ and find their screening tool, confidential phone line (1-800-931-2237), and online chat support option.

Leave A Comment