Foster Care & The Shame Spiral

Lisa Marie Basile

For as long as I remember, loss was the ghost that haunted my world. I knew it too early: as a child, my parents both used drugs and fought and struggled to pay rent. We’d move from house to house, and then to homeless shelters—with my father eventually leaving and being imprisoned—and my mother falling deeper into a well of addiction. She tried her hardest to keep us, but life has its own path.

Eventually, as a teenager, my brother and I ended up in foster care, separated into two separate homes after living in a dark, dusty attic with extended family for some time. I’d lost everything and everyone I knew. My precious, teenaged belongings—my CDs, my childhood stuffed animals, my bed and dresser, my diaries and scribbled pages of poetry—was gone. It had vanished to the many moves and homeless shelters, lost in the shuffle of time and disease and volatility.

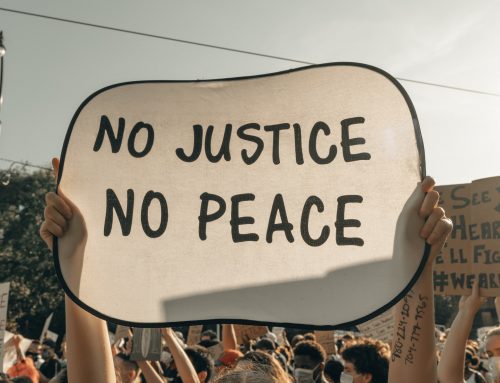

For those of you wondering: Do you have to talk about your parents like this? The answer is a resounding yes, quite simply. I am very close to both of my parents today—and they are both in sustained recovery—but these details will always have to be told in order to tell my story. And my story must be told in order to free myself, free others and break the larger stigmas associated with addiction, homelessness and foster care.

Before foster care, I had no idea what it was—that the state’s powers that be could simply decide your parents weren’t good enough and that you could be taken away. I knew we were always on the verge of eviction because my mother couldn’t really hold a job in her attempts at getting clean, but I didn’t think it could get worse after the homeless shelters we ended up in when I was about 12.

But it did. After living in a tiny room on the third flood of a domestic woman’s shelter, and then at the YMCA, and then in an outpatient house, my mother had tried again to clean up…but she lost us. Foster care was what comes after homeless shelters, I found out. I was to become a “foster kid.”

It was like strapping on a pair of wild, black wings and walking into a school of normal, happy children. I was loud and clucking, feral and scary. They could smell the difference on me. The way I dressed differently—i didn’t have expensive sneakers or cool clothes. The way I sat in the back and read my books, not trying to socialize. I felt lonelier than I’d ever felt before, but the sadness was so immense and so all-consuming that I didn’t feel sad about it. I simply was the loneliness, had become it, had been embodied and inhabited by it. I just drifted along.

I’d keep myself pretty separate; I’d write instead of join classmates. I’d skip class to walk outside. I made friends with teachers who felt like parental figures. I was, in a way, growing, building strength and selfhood—not letting high school distract me. I had a wound. My priority was to tend to it.

But that came at a cost: the stigma attached to me was real. People either felt bad for me or they were fairly weirded out by me. They’d heard through someone that I was “staying with some people as a foster kid.” I was once called a boarder—and this cut right through me…because it was true.

My foster family was well-known in town; they managed a school for performing arts and anyone in town who had anything to do with theatre knew them. Whispers made their way around about me. I was strange, poor, my parents were “crackheads,” that I was a juvenile delinquent. I wasn’t poorly behaved—but so what if I was? Even my high school guidance counselor told me I’d never get into college. (I got into every single school I applied to (for writing) for the record—off the back of my excellent writing samples and English grades).

Sometimes I think back on that experience and wish I had had language with which to address the stigma—to say, “hey, I heard you telling someone I was X or Y…would you like to know the real story?” or “I heard you say X or Y about foster care. Would you like to know what it’s like for me?” or “I heard you say these awful things about drug addicts, but I think there’s more to the story…”

Of course, there’s no way I could have had the grace or courage to speak up then, and I can’t blame my younger self for not. She was afraid, she was hurt, and she was holding herself up as best she could. She had no emotional labor to dole out to others.

Today, I do. That’s why I’ve written for The New York Times and Narratively and The Fix and The Huffington Post. That’s why I’ve started a magazine called Luna Luna. That’s why I speak out. I want to make it clear that all addicts aren’t bad people. They’re sick. That homelessness is a systemic issue affecting many, many people of all walks of life—and that one’s homelessness isn’t an indicator of their worth or value. That foster youth aren’t all criminals or “bad apples.” That we have feelings and fears. That we’re real. We’re made of flesh and blood. That some of us have found ourselves in a system that projects its perceptions of us onto us—which can ultimately be fulfilling if internalized and without support. And that some of us, despite what have happened to us, have a voice and the resiliency to rise. We just need a platform or a friend or an advocate to say, “Tell your story. It matters.” Telling your story makes space for others to be free. Telling your story beaks stigmas. Telling your story ends the shame spiral.

So, I want to say this to you—no matter your struggle or background, no matter your mistakes or traumas: tell your story.

It matters.

Bio: Lisa Marie Basile is the creator and director of Luna Luna Magazine—a digital diary of darkness and light, art, identity, and witchcraft. She has written extensively about overcoming grief and trauma, managing chronic illness, body positivity, wellness, witchcraft and poetry. She is also the author of a few books of poetry. Lisa Marie’s work has appeared in the New York Times, Narratively, The Fix, Refinery 29, and more. She earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University. She lives in New York City.

Lisa Marie this was beautiful. I could relate to so much and you opened my eyes to the things I couldn’t relate to. I love the part where you say, “all addicts aren’t bad people.” If only the rest of society could understand what you wrote, that would help change so much in our world. But thank God for writers like you and places like Stigma Fighters! Together we can help break this. Beautiful writing and congratulations on all of your success.