February 3, 2019

“Transformation is achieved through suffering alone.”

– Buddha

“Only through utter defeat are we able to take our first steps toward liberation and strength.”

– Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions (Alcoholics Anonymous)

Since I was a kid, I’ve been treated for what used to be called dysthymia, and is now know as Persistent Depressive Disorder. When I say “treated”, I mean dealt with or tolerated. I isolated from my family and erstwhile peers using illness and my relationship with the almighty god of television as my implements. Strep throat, real or imagined, is a worthy tool when you’re five. So is the Carol Burnett Show.

Visits with a series of therapists began after an incident where I holed up in the attic and went through family photo albums, obliterating my own face with a drafting razor in picture after picture until I had all but erased myself. It was artistic violence. I remember the seven-year-old me taking shivery, belly-satisfying comfort in the action. It was a less-extreme version of “cutting.” Rather than slicing my actual flesh as some do, I hacked instead at my image. I’ve always been an expressionist, a representationalist. My swift, angry, imprecise cuts focused on the obliteration of my eyes. Our eyes are how we see the world, but they are also, proverbially, the window to our soul.

My representationalism ended when I met crystal methamphetamine and discovered a way to feel joyous and to genuinely harm myself at the same time. It was as if meth, and a particularly damaging way of administering it, were invented just for me.

I was not a drinker as a teenager. A witness to my father’s confused and fumbling alcoholic behavior, I feared even beer and avoided it and the social situations where its consumption might arise. I didn’t try pot until my thirties and, even then, felt dirty and ashamed for toking.

My first direct contact with crystal happened at forty-four. I’d had several boyfriends, and even a husband, succumb to meth and it’s lure. One of the loves of my life, a Broadway star, died by hanging himself in a barn in Australia during a particularly nasty comedown from the drug. Throughout my adult life, I’d treated meth with the sort of deference one would give a rattlesnake poised to strike, its slender, pointy fangs ready to puncture.

But then it was my turn. Dumb curiosity got the better of me. I first smoked, and then with great enthusiasm injected, the drug that was to be my undoing. I grew evangelical about it: my love of meth was pathological and consuming.

“You won’t see it taking over your life until it’s too late and the story is already written,” my husband T.J. warned in a rare moment of clarity, fortune-telling with chilling accuracy. “You’re going to lose everything—your work, your house, all that you’ve worked for. Relationships. People counting on you and trusting you.”

What did he know? He hadn’t dealt with lifelong greasy-gray emotional weather, where every day came with a forty percent chance of showers, or maybe it was thirty-three and a third (precent?) rpm, a crackling LP record where I never quite reached the halfway mark where things felt basically okay. What did he know? T.J. had been a smiling child, not prone to crying jags, made-up illness and hiding under the bed. Though were we were swilling the same medicine, it was a cure for different ills. His malady was mere awkwardness, I decided, whereas mine was an unshakeable funk, an irrefutable fog.

Crystal Meth made me Superman. Super sexy man, able to leap tall nearly-anythings in a single bound. And it made me sweat. And it made me awkward and short of breath. I could hear myself gasping in voiceovers. And it made me frightened and then paranoid and then psychotic. I noticed. And people noticed. Employers noticed. Friends noticed. Employers left me and friends left me. And my beautiful house because a haunted, shadowy place populated by haunted, shadowy people, half-alive, half-dead. I half-knew then half-forgot them and blamed them for my growing list of woes and grievances.

My husband and I fought daily. At the peak of a meth-fueled quarrel, he ran me over with his car, leaving me with a marionette version of a right leg and, four knee surgeries and a hip replacement later, partially disabled.

A five year decline ensued. At times I leveled off—think of a roller coaster clattering along the tracks at a boardwalk amusement park—and then there’d be another precipitous fall during which I gasped, raised my arms, and was released from gravity. But this coaster did not loop back to its origin, instead dipping lower and lower. Nobody got off, giggling and rubber-legged, to pick up a giant stuffed animal and make their way to the next ride.

There was no more ride. (There was more car.) And then there was no more place to live, to pretend that things were still okay. There was no more bed to hide under. There was no more anything but rock bottom.

“Rock bottom” — what a gorgeous term that is! It’s not really a place so much as a moment of reckoning. You find yourself facedown in a mud puddle, aching and humiliated, and you realize you can’t lift yourself up to breathe, much less stand. You are between a rock and a hard place and that hard place is everything in existence, everything you can feel and see and know and remember and imagine. And you want to die. Or you are dying. Or you are dead. Only no, you’re not dead because you are suffering mightily. And for all the heaviness there is a lightness because you have transcended anything reasonable. You have broken through to where you are, the pain and the pain is you.

At at this juncture, you either perish or you begin the slow and arduous process of recovery, something which feels nothing like “recovery” and everything like chewing broken glass.

And that is where I am. Fourteen days ago I lost my housing as a direct and indirect result of using crystal. The friends with whom I’d been staying for months, with the intention of adding sober days and growing my employment, put me on the sidewalk along with a pile of wet laundry and my beleaguered dog and called the sheriff in order to hurry me along.

Fourteen days ago, I became abruptly sober, like it or not.

Fourteen days ago I sat alone in a cold, rocky field alongside the 101 freeway in Nipomo, California, laughing (but no, not laughing) and undone. There was wailing and flailing in the place of words and composure. I had a spiritual grand mal. What terrified me most was my inability to quit, to button things up, to make my face untwist from that of a spectral ghoul into something human. Shivering hours passed. I ended up at the Emergency Room of Marian Medical Center (about which I cannot say enough good) and a day and a half later, through the auspices of Santa Barbara County Department of Behavioral Wellness, at Good Samaritan’s Bridgehouse emergency homeless shelter in the nearby town of Lompoc.

It is only in the last seventy-two hours or so that I’m beginning to be able to think straight, stand up straight and walk in a straight line. I’ve been to church twice this week and, last night, led my first ever Narcotics Anonymous meeting at the shelter.

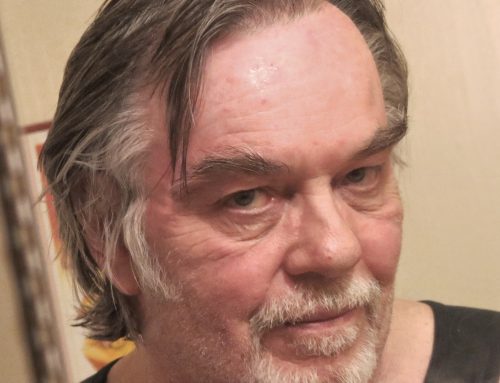

My name is Ben Patrick Johnson. I am a homeless American. I am sober. I have found “rock bottom” and with it, I pray, bedrock.

Now, the real work begins.

I hope each day become more peaceful for you, never give up.

Thank you for letting us know what has happened. You are a good person and we support you. The Gift Of Desperation. Time for healing dear friend.

Ben, your writing is intelligent, lyrical, honest. It reveals your resilient spirit…and your innocence. There’s humility in there too, which is one of the most precious gifts a human has access to. Thank you for finding that humility when you went searching at your “rock bottom.” Thank you for your courage. Thank you for your suffering. Thank you for sharing the grit and the gruel —and growl—of your life with us.

I love you brother Ben.

Your sister Susan

You are in My prayers daily.

You got this bro.

God’s got you!

Hugs and continued healing. Happy you’re here and telling your story. I struggled with this for years, you can put it behind you, hard as it may be. Always look forward, the past is behind you now!

Ben, sending lots of loving energy of peace and healing your way! I have been there as well. Thank you for sharing just a private moment with us.