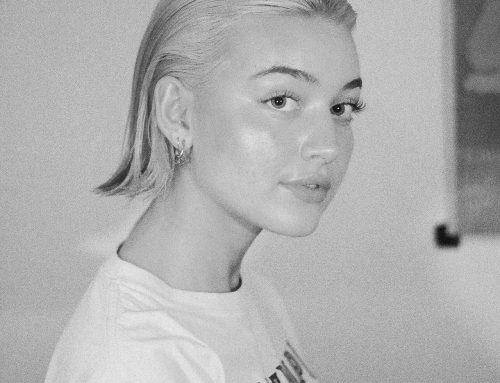

Kevin Hall’s ruminations on his own suicidal thoughts.

Yesterday—in front of my two younger children—I nearly choked to death on my grilled chicken dinner. What should have simply released a heavy sigh of relief in my wife’s ear at bedtime contorted into a sleepless night of revisiting another recent near miss: Last month I wanted to take my own life.

The two brushes with death are incredibly same, but different.

Similar, in the end result: cold bodies either way.

But different, in the legacies:

The choked version simply was seeking nourishment. That nourishment took an unfortunate wrong turn at the split between esophagus and trachea, blocking the proverbial airway. The mechanics are well understood.

“Accidentally choked to death” is relatively straightforward to say to a stranger. It carries no moral overtones. Yes, it was the recently deceased who put the food in the mouth, but Joe Doe is absolved from that moment onward.

On the other hand, “Accidentally died by suicide” sounds like a phrase that might be used in a really bad standup routine, or maybe a Darwin Awards situation. It doesn’t ring quite right, even for me as I sit here trying to advocate the perspective-giving potential of thinking of death by suicide as accidental, like choking on chicken at dinner time.

I allow myself to think: suppose I didn’t make it last month. Suppose that, instead of going into respite, I had driven off a cliff like my troubled mind kept telling me to do. Suppose the pivotal nourishing thought went down the wrong pipe, so to speak.

Friends and peers, some time after the initial anger subsided, would perhaps have written things about me. Maybe those things would transmute the grief and transcend the impossible-to-understandness of suicide. Or, maybe they would read more like Jonathan Franzen’s New Yorker article eulogizing his friend David Foster Wallace. It was written two and a half years after David’s death:

“He was sick, yes, and in a sense the story of my friendship with him is simply that I loved a person who was mentally ill. The depressed person then killed himself, in a way calculated to inflict maximum pain on those he loved most, and we who loved him were left feeling angry and betrayed. Betrayed not merely by the failure of our investment of love but by the way in which his suicide took the person away from us and made him into a very public legend.”

I don’t know Mr. Franzen, and I didn’t know David either. But I do know that when I have been just a chosen chicken bone from death, it has been calculated to RELIEVE my family and friends of the supposedly-interminable ineluctable burden of supporting a depressed person, day after day, with no laughter, considerateness, or even personal hygiene in sight.

I recoil every time I re-read Mr. Franzen’s words. Perhaps I am missing the context which softens them, in which case I do hope he or someone else will write to me and fill me in.

I can’t speak for everyone who has died by suicide. What I can say is that when I’ve drawn another breath instead of leaving the planet, it has been more like an accident than a willful choice.

And the accident is to forget, for the briefest of moments, that part of my own family has told me they’ve felt “disrespected by my mental illness behavior.”

The accident is to forget that people think I should just “try harder” when I am depressed.

The accident is to forget the ubiquitous shame and stigma around mental illness.

To forget that the medical model essentially says I’m broken until medicated.

Suicides are perpetrated to relieve, not to inflict, maximum pain. What bystanding survivors (clearly) don’t easily see is that it is their pain which is targeted for relief.

Kevin A. Hall is an Ivy League graduate of Brown University, and despite being diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 1989, he went on to become a world-champion Olympic sailor, as well as racing navigator for Emirates Team New Zealand in the 2007 America’s Cup match. A two-time testicular cancer survivor, Hall has spent a successful 25 years as a racing navigator, speed testing manager, and sailing performance and racing instruments expert. His memoir, Black Sails, White Rabbits; Cancer Was the Easy Part is Hall’s first book. He currently lives in Auckland, New Zealand with his wife and their three children. www.kevinahall.com andhttp://www.testicularcancersocietyblog.org/survivor-spotlight-kevin-hall/

—

This post is part of a joint series by The Good Men Project and Stigma Fighters in sharing stories of real men living with mental illness. To submit your story, see below.

Stigma Fighters is an organization that is dedicated to raising awareness for the millions of people who are seemingly “regular” or “normal” but who are actually hiding the big secret: that they are living with mental illness and fighting hard to survive.

The more people who share their stories, the more light is shone on these invisible illnesses, and the more the stigma of living with mental illness is reduced.

The Good Men Project is the only international conversation about the changing roles of men in the 21st century.

The Good Men Project is the only international conversation about the changing roles of men in the 21st century.

Mental health and the reducing the social stigma of talking about mental health is and has been a crucial area of focus for The Good Men Project.

If you are a man living with mental illness, and want to share your story, we would love to help.

To submit to the Good Men Project, please submit here.

To submit to Stigma Fighters, please submit here.

Submissions will run in both publications. When you submit, please make sure to let us know you submitting as part of this Joint Call for Submissions with Stigma Fighters and Good Men Project.

Leave A Comment