My Life As An Obsessive

by Lauren Osborn

I hated my psychiatrist, his smug, clean-shaven face like a map that hadn’t been colored in. Photos of his immaculate wife and his pristine children glared at me from inside their well-polished frames.

“Tell me about these thoughts,” he said.

But where could I begin? How do you go from being a seemingly normal person to one who admits to fearing for her mortal soul on a momentary basis?

“I’m afraid if I don’t do things in a particular way, the devil will have my soul.”

“That’s normal,” he said.

Normal? I don’t fucking think so.

There was a time in my life I would later refer to as my desert days. If you’ve ever been really depressed or anxious, you know how painfully isolating it can be. You feel shipwrecked, waiting for a rescue that may never come. For me, it was a desert. I wandered alone, exhausted, in a place where no one would reach me — my twisted mind.

I was terrified to leave my desert because I was unable to cope with the actual world. Holding a conversation was virtually impossible because the record in my head would not stop turning. With every breath came the overwhelming weight of impending doom. My journal tells the story best, riddled with cross-outs, unnecessary punctuation, rewrites of the same words and nonsense phrases, my handwriting alien. Was this me?

To clarify, obsessive-compulsive disorder is different from depression and anxiety, yet encompasses both. “If you don’t swallow at least 16 times in sets of 4 right now I’m selling your soul to Satan for all eternity,” my mind drones as I stare blankly at my dinner, breath held as I finish my compulsion before eating. If I mess up the counting or swallow “incorrectly”, the whole process must be repeated. And here’s the thing: I know these fears are irrational. It’s highly frustrating to be a logical person who has no control over her tumultuous mind. I feel hopeless.

Early on, the compulsions became time-consuming. Most of my day was ruled by my rituals. The worst was that my symptoms appeared early. As a child, neither my parents nor I knew of OCD. My irrational fears, constant crying, extreme perfectionism, and repetitive patterns were treated as eccentric behaviors of a highly intelligent child. While my parents turned a blind eye to it, I suffered, oscillating between thinking I was schizophrenic and thinking I was possessed. To say I could not relate to my peers was an understatement. By the time I was 12, I had attempted suicide.

I can distinctly remember the day I cracked. The gorgeous day only mocked me as I looked myself in the mirror. Lovely eyes. Eyes like my grandmother, this towering relic I never even met. Like her looks, her legacy lived through me. Unfortunately that legacy was one of mental illness. I didn’t inherit her sapphires or diamonds but her unconquerable sadness, a penchant for odd behavior, empty eyes green like sea-glass. Once they glowed and now they reflected an unending, hollow depth. Was I just like her? Would I too take my life because it was humane?

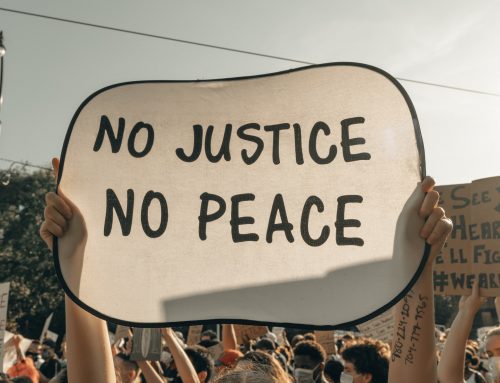

One thing about OCD that people do not understand: it never goes away. There are periods of improvement, but it is a chronic illness. It is not psychosomatic and it cannot be controlled with “enough willpower”. This is a highly nuanced disorder with biochemical and genetic components. There is no screening process for OCD, no cure. And I’m not alone. About 1 in 100 adults suffers from OCD, and 1 in 200 children. This means someone you know is probably dealing with this psychologically ravaging disease, carrying shame and embarrassment like a sack of bricks.

If what we don’t understand we tend to fear, then the societal fear of mental illness must be due to lack of understanding. For years my OCD went undiagnosed, never taken seriously because no one really knew about it. With more research, attention could finally be brought to the science of the disorder and help lessen the stigma. While I know that few could ever truly understand what my life with obsessive-compulsive disorder is like, I hope that some can gain respect for this terrorizing illness through knowledge of just how real it really is.

Lauren Osborn is a 27-year-old freelance writer and photographer in Austin, Tx. Lauren was officially diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder at age 18, and still struggles to remember to take her pills. Her writing focuses on feminism, mental health and the Great American Dream – and the intersection of the three. Much of her work surrounds creating an open dialogue about mental illness in order to humanize it. First published at age 10, her work has been featured in countless literary magazines and two books, under both her real name and pen names. She has a soft spot for redwood trees, her zealous cat, Sir Henrich, 60’s counterculture, and her urban family. Her ramblings can be found at: http://laurencosborn.

I have often felt my doctor/therapist was just mocking me with all the success and perfection they had. I would fight with them just to feel like I was “better than them.”

I am glad you posted. You are brave and awesome. 🙂 Gabe

You write beautifully Lauren about a really painful and life-altering condition. It’s hard for me to believe that no one diagnosed you, but as you relate, there are practitioners in my field who are just bad. I regret that you suffered because of that. I have shared your story on my own Facebook page. My mother, by the way, also suffered from OCD. She didn’t do well either and ended addicted to prescription drugs. Thank you for writing what I know will help others.