Free

The first time I thought about killing myself, I was seven or eight years old. My parents had recently separated. With their separation, the thin film that had kept me from falling into a dark hole wore through. In fact, I had reoccurring dreams about it, about a hole, in our front yard, sucking me under, and no one would see me disappear. That hole held all the feelings that set my brain on fire.

What I said might be a lie, not about the hole, but that the first time I thought about killing myself I was seven or eight years old. Because I was younger. I had trouble sleeping from about the age of four. Coincidentally (not really, it wasn’t a coincidence), it was also around the time that I was sexually abused, by an adolescent boy, a friend of the family. I don’t remember the sequence of events, because my memory pushes them together in an accordion that folds and unfolds involuntarily. But, I do know that around that time, when I couldn’t sleep, I would keep my body as still as possible, holding my breath, counting the seconds, wondering if I could hold it so long that it would stop- my breath, and everything.

The first time I felt any real relief from the threat of that black hole, the one that followed me around sucking and smacking at my feet, was when I stole an expired Darvocet, an opiate, from my mother’s medicine cabinet. My mother didn’t take them, they were leftover from one of my grandma’s hospital stays. I didn’t know what it was, but it was large and red and it called to me from the bathroom shelf. It worked. I didn’t kill myself that night, the hole shrank away, where I could still see it, but it couldn’t touch me.

Over the next few years, any time I felt that darkness nipping at my heels, I’d steal a pill. I became gifted at sneaking a Valium or Vicodin, or okay maybe two, from medicine cabinets whenever I used someone’s bathroom. As I approached my thirteenth birthday, I felt increasingly stifled by that black hole of depression. My father was distant, both literally and figuratively, and my mother, while loving, was embroiled in the soap opera of her personal life. Then, I tried heroin.

I was thirteen. My boyfriend was sixteen. He offered it and I didn’t hesitate. To the outside world, I was doing just fine, no better than fine. I was popular, got good grades, was involved with horseback riding and cheerleading and volleyball. But, I did heroin on the weekends and stole pills and started cutting myself.

Throughout my teenage years and into my early twenties, I used heroin off and on, I cut myself off and on, I stole pills. And, I hid that layer beneath my skin that held all the secrets and shame and fear, from nearly everyone around me, including friends, boyfriends, parents, and therapists. That pulse of depression became so strong at times that I literally had to sit on my hands to prevent myself from giving in and killing myself, digging my nails deeply into the backs of my thighs until I bled.

My heroin use escalated sharply at age 23, I got caught, and went to my first rehab. The focus became the addiction. And, I relished it. It was a relief. I wasn’t crazy! I was a drug addict. I had felt so ashamed for so long about using, but then when it was out in the open, it gave me a reprieve from the other thing, the bigger thing, the one that kept me up at night, that kept me running in all directions and into walls. No one could know what was really wrong, that I was crazy.

For five years, I went through a cycle of relapsing until I got to a point so low that I stood on the roof of a building, strung out on heroin, and up for days smoking crack, watching the city beneath me, knowing that I had to decide if I wanted to live or wanted to die. I wasn’t sure, but I knew something had to stop. A feather-weight difference in the right direction led me to reaching out for help and going back to rehab. It was during this second trip to rehab that I first began to admit that the drugs were a symptom, that the problem was my brain.

That was the beginning of getting well, but it has taken years for me to get to where I am today. Even after I had my son, functioning well as a mother, off of drugs for almost a decade, I found myself across a table from the man who would become my husband discussing my mental health. I had been acting out, in destructive ways, sabotaging the good relationship we had. He laid it on the line and told me that he loved me, that he wanted this to work, but that I needed to get help, I needed to address my mental health issues, or we were through. I heard him.

I went back to therapy, got back on medication that I should have stayed on before, and my life began to fall into place. FINALLY, after more than thirty years of holding my breath, counting, wondering if I could make it all stop, I faced that black hole that lingered at my feet. Sometimes I spy it, from the corner of my eye, but instead of running, I stop and wave. I talk about, write about, am honest about my struggles with depression and about the years I spent using drugs in an attempt to try and “fix it,” and I have no shame. I never thought I would be able to say that. Sure, there are things I look back on and am not proud of, but I no longer hate myself for any of the mistakes I made along the way to becoming who I am today. Because of that, I am free.

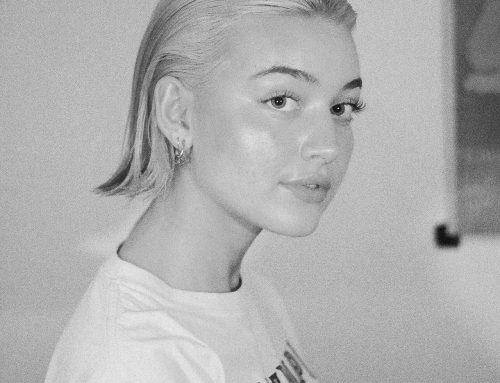

Erin Khar lives, loves, and writes in New York City and sometimes other cities too. She was the recipient of a 2012 Eric Hoffer Editor’s Choice Prize for her story, “Last House at the End of the Street,” which was published in the Best New Writing 2012 anthology. Her work has appeared many places, including Marie Claire, The Manifest-Station, Sliver of Stone, Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood, Esquire, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan, and as a regular contributor for Ravishly. She is currently working on her first book, a memoir. When she’s not writing, she’s probably watching Beverly Hills, 90210.

Erin Khar lives, loves, and writes in New York City and sometimes other cities too. She was the recipient of a 2012 Eric Hoffer Editor’s Choice Prize for her story, “Last House at the End of the Street,” which was published in the Best New Writing 2012 anthology. Her work has appeared many places, including Marie Claire, The Manifest-Station, Sliver of Stone, Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood, Esquire, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan, and as a regular contributor for Ravishly. She is currently working on her first book, a memoir. When she’s not writing, she’s probably watching Beverly Hills, 90210.

Leave A Comment