On Choosing Life

When my mom made an appointment for me to talk to a therapist after my boyfriend and my father died within four months of each other, it instigated yet another explosive argument.

“I’m not crazy,” I shrieked at her. I did a lot of shrieking back then.

I was so terrified of the word therapist. The idea of therapy; of talking to someone whose job it was to get inside the mess of my brain. I imagined a stranger uncovering each damaged thought and using my words against me.

I remembered a made-for-television movie my mother had let me stay up to watch a year or two earlier. A woman suffering through bulimia was a dangerous, out of control thing. There was evidence used to force a confession and the movie wrapped up with her moving towards healing. But honestly, I didn’t think of the ending; I didn’t even remember it. What I remembered was the capture, the a-ha moment when she was cornered into admitting her illness.

I was terrified of being found out in the same way. Terrified my therapist would see the scars etched into my wrists, shallow cuts that were more remembrance of life than intent to kill. That I would have to stand trial of sorts, evidence of self harm and self loathing convicting me of mental illness.

Once convicted, I would be sentenced to a lifetime in and out of dirty, desperate institutions. I’d be sent to Kahi Mohala where I would be one of “those” patients my friends and I ridiculed. I would spend days in a straitjacket. At night the angry chatter of my brain would be amplified by the yells of the patients around me.

I could not let that happen.

Two days before my first therapy appointment, I made my first suicide attempt. Fortunately I didn’t have anything stronger than headache medicine, but the intent was there. For the very first time, I actually wanted to die. I didn’t even get sick enough to warrant a trip to the hospital, which made me feel like a ridiculous failure. I cleaned up after myself, endured acute shame and nausea in the elevator to my new therapist’s office, and never spoke a word of it to my mother.

I didn’t speak a word of it to my therapist either, though I answered her questions as she went down the intake form my mother had filled out.

“Your father died recently?” she asked sympathetically.

I nodded, and told her that my father’s death had come after a long illness so it wasn’t a shock. The real shock was my boyfriend’s unexplained death four months earlier.

“Oh,” she said, looking back at the form. “Your mother didn’t mention anything about that.”

“Typical,” I told her, bowing my head.

She sized me up for a moment. Looked back at the form. She put her clipboard on the table and didn’t look at it again for the rest of the session. She did look at me, though, asking questions in ways that made me realize just how much I wanted to answer them. How much I wanted to talk about this. Wanted someone to listen.

Still, I was convinced that opening up too much was impossible. Perilous. I had in my mind everything I’d ever seen in movies or on television about crazy people. Books I had read about girls being taken against their will to languish in mental wards that were more like prisons.

I knew that would happen to me if I let anyone in.

And so, for the most part, I didn’t.

I never shared with my therapist the self harm, the suicide ideation. The longing to be rid of everything and everyone, beginning with me. I told myself that I wasn’t like the girls in books and in movies; awful girls I hated with a kind of externalized self loathing. It wasn’t like that, you know. Didn’t deserve lock-down they way they did. I wasn’t, you know, crazy.

So when the dark thoughts came again and again, pushing me to carve angry wounds into my skin, to drink until I felt nothing but sickness, I did the opposite of what I needed: I stopped seeing my therapist. For the next eighteen years, I struggled to contain my darkness. I did not succeed.

When I was hit full force by stillbirth in 2009, the trauma spiraled me immediately into new depths of mental illness. I began hallucinating, suffering through terrifyingly graphic intrusive thoughts. I thought about self harm constantly, and dreamed of it when I was asleep. There was no respite in my abyss. I knew I was courting suicide.

Desperate to stay alive, I made an appointment with my doctor. Her kindness had guided me through the medical trauma of pregnancy loss, and I trusted her. I left that appointment with a scrap of hope disguised as the phone number of a therapist, and the determination to actually call it.

I have been seeing that therapist ever since.

Having an advocate, someone whose sole responsibility it was to talk to me through all of the vile, repetitive awful I had come to expect from my angry brain, was a revelation. Difficult, of course, and I’d be lying if I said I don’t still harbor a sense of impulsive self-protection that keeps me from spilling all of my secrets. Of course I do. I carry a strong sense of shame, of internalized stigma, with me to each and every one of our exhausting sessions. It makes our work that much more difficult.

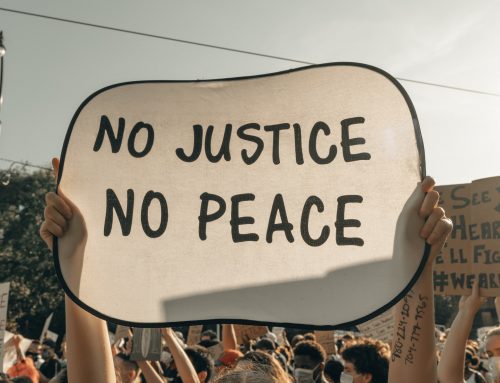

For years I harbored an erroneous perception of mental illness, one that I used to judge myself and others. That perception took years to create, and will take years to fully dismantle. Realizing it was stigma preventing me from seeking the help I needed when I was fifteen, I cried for the girl who so desperately needed protection. I also realized that unless I wanted to look back on my thirties with the same kind of tears, I needed to do the work of combating stigma now. I could choose to hold on to my sense of poisonous judgment, or I could choose to save my life. It was just that simple.

I chose life. Every word I speak about mental illness is a continuation of that choice. Every raw, brutal word I write is a lifeline; a weapon in the fight against the injustice and dishonesty of mental illness stigma.

And I will never, ever stop fighting.

Celeste Noelani is the woman behind RunningNekkid.com, where she explores the intersection of grief, mental health, and her Pacific Islander ancestry. She left her home in paradise over twenty years ago and has been trying to figure out how to get back ever since.

What a journey. How much strength it must have taken to go through so much and finally have the courage to trust and the bravery to get that help. The stimga is such a tricky beast. It whispers and tells lies and it keeps us from seeing the beauty, the person. How wonderful that you shared your story so that we too can see past the mental illness the beauty and the person there is in people.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Carrie. It really had been a long journey and I feel so fortunate to finally find places like Stigma Fighters where I can come to share, and feel less alone.

I hope you are doing well.

I’m so proud of you for always sharing your beauty and insight about mental illness. You are a stigma fighter Celeste.

Thank you so much, Cristi. I’ve learned so much from your brave example these past few years. <3