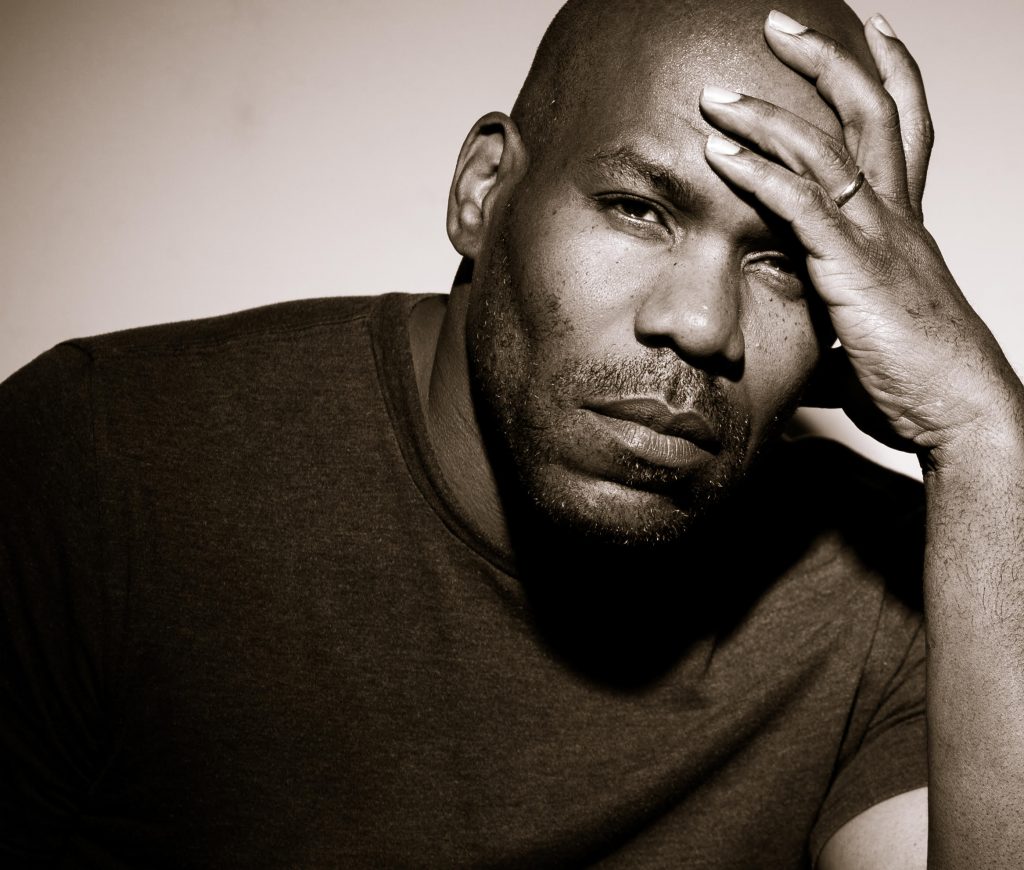

When my wife, Ann, was officially diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder, it was not the major revelation that one might expect. It was a label to the problem I had been dealing with since she left Silver Hill Hospital. I knew something was amiss. Despite the weekly double session therapy she’d been attending faithfully and her compliance with her medications prescribed for postpartum depression, she wasn’t getting better. Bipolar Disorder gave a label to the “something” insidious creeping ever so slowly, artfully, into our household.

I had seen the writing on the wall for quite some time. I knew there was something wrong. I could see the subtle changes compounding on each other, ultimately becoming a glaring sign. The Bat signal had been raised, only we didn’t live in Gotham and Batman was not coming to the rescue. I was left to figure out how to navigate this “something” while keeping our kids insulated from their mother’s illness. I made sure the household kept running smoothly and our secret was safe.

In the early months when we believed it was severe postpartum depression, I felt I had to lie when asked about Ann. I did this because I couldn’t let her/our truth out and have people think less of her. I lied because I could not let our children know why their mother was unable to look them in the face or spend time with them. I lied because I didn’t fully understand the illness myself, even though I tried to. I read multiple books and article online, attempting to gain an education on postpartum depression. I lied because deep down I knew this was something more. I lied because I knew of the stigma that came with her diagnosis and I wanted to shield all of us from it. Most of all, I wanted to shield Ann from being labeled “crazy” post-hospitalization. I needed to shield the boys from having a “crazy” mother. The stigma of mental illness kept us isolated.

The great cover-up continued as her condition worsened and I gained more understanding of what was actually happening. Now that a formal diagnosis was established, I was able to communicate with her caregivers from a more assertive position. I knew what questions to ask. I now knew what signs to watch for at home in order to gauge her stability. That was the easy part.

The challenging part for me was being both mom and dad. I was the maid, cook and caregiver with no help from Ann. First, she dealt with being sick. Now she had to deal with getting better and at times that meant being in the hospital away from us. My mom, sisters and brother-in-law helped whenever they could but it was still a hard road. The stress mounted further when her team of providers were unwilling to put a timeline on the length of her hospital stay. I wanted to figure out how long to have babysitters or to call in for extra reinforcements. I refused to let Ann be alone in the hospital. I refused to miss a single visiting hour even with all the responsibility at home. I took a vow to stand by her in sickness and in health. I was not complaining to the hospital staff that I had my kids. I was asking for clarification in order to determine how to best take care of our family.

I was astonished by the openly hostile attitude I received from the Emergency Department physicians the first time I walked in after Ann’s first overdose. One of the doctors let out a snide remark “Oh, you finally made it.” He said. This was judgmental and lacked understanding of my family’s situation. We have three children that needed to be cared for while I was at the hospital sorting out what happened to my wife. The hostility on behalf of the hospital staff persisted when I once told ambulance staff that I would NOT be riding with them. I could NOT leave my children alone. The EMTs, in turn told ER staff that the kids were by themselves at home, resulting in a full-scale DCFS investigation into their welfare. A DCFS officer and police officer banged on the door at 8 pm as the kids were getting ready to go to sleep for the night. The sheer callousness of the hospital staff was astounding at times. Once Ann asked to wet her throat because it was dry and they refused telling her “You shouldn’t have overdosed or you would not be in this predicament.” Ann was ill. She wasn’t on the proper cocktail of medications. Ann, when she is stable, is not in “this predicament.”

I’ve had to make some difficult choices regarding our family that Ann’s therapist didn’t always agree with. These were decisions that the treatment team did not feel were in her best interest even though I felt they were in the best interest of our family. Looking back, I was 100% right to stand my ground. I understand that her health was (and is) the most important matter to them. However, it’s frustrating and disappointing when the family of a mentally ill person is seemingly left hanging.

Ann fought hard to get better. She signed papers so that her therapist and psychiatrist could communicate with me freely at any point. Yet, if I called with concerns or questions for the treatment team, I was greeted with hostility, a guarded manner, and received only the most basic answers.

No one considered the family of the mentally ill person. I was left to handle everything alone. However, mental illness is very much a family-centered illness. If Ann had cancer, I would have casseroles and support groups coming out of the woodwork. It simply does not exist in the mental health community due to the stigma that all family members feel just as acutely as the actual patient. They are fearful to speak out and reveal the secret they worked so hard to protect. It’s time for the families to speak up and talk about the effects of the illness on them too.

I pray every day that families become a priority in the care of mental illness. It’s hard having to manage a household by oneself while your loved one is in an inpatient facility, but I did it. I kept everything running smoothly. The kids were happy and I made sure they knew they indeed had TWO parents loved them very much, but one was ill and simply unable to show that love temporarily. I did all of this because I love my wife and my boys and I believe in our future.

Keith Roselle is a husband, father, graphic designer and photographer living in Bethany, CT. His work can be seen at keithphotography.virb.com

He has passed on his love of superheroes and comic books to his three boys and his wife. When not fighting the good fight of mental illness advocacy and reform he can be found on the baseball field or the local ice cream parlor. Instagram: @keithroselle

This article originally appears on The Good Men Project. This is part of a collaboration between Stigma Fighters and Good Men Project.

Leave A Comment